Hey friends 👋🏼 Startups are games. This newsletter is about empowering brains (with startup game theory) & hearts (with intros + celebrations). Today, we do the former: this multi-part article will be about running our first startup simulations. 😎

⚡️ Bottlenecks KILL momentum. Let the network unblock you fast

Struggling to hire a 100x engineer?

Looking for intros to investors or customers?

Facing a hard decision with no expert to call?

Every week you delay costs momentum.

You don’t have to do it alone.

This network exists to tilt the odds in your favor — with 5,000+ sharp founders, operators, and investors ready to help.

👇 Fill this in — it takes 30 seconds, and someone smart will reach out.

🎯 Hire Globally Without the Headache (Partner of the Week)

Is your workforce spread across multiple countries?

If yes, then you should consider using Deel to save some money & time.

They seem to be one of the biggest players in that space: they are used by 25,000+ customers worldwide, from seed to unicorns.

If it makes sense for you, see their demo & see if it makes sense for you (note: you get preferential fees by coming through us). 👇🏼

🧮 GTO Moves - Optimal Product vs Distribution Balance? Part 1

Founders play multiple games in parallel, e.g., hiring, distribution, fundraising, PR, among others.

While not everybody plays all of them, there is one that everybody plays: the fundamental game of startups.

Last week, we introduced an important hypothesis that will make it possible to run simulations.

This week, we’re going to set up a simulation to address one of the biggest questions for early-stage ventures:

“How to optimally balance distribution versus product to win?”

This is part 1 of answering this question.

Teaser: I haven’t met a single founder who gets this right.

1) Modelling the situation

“A model is a lie that helps you see the truth.”

We’ll study the following simple situation:

You’re an early-stage startup in a mature market, competing only against a big incumbent and another startup.

Recalling the definition & framework of the fundamental game, we now have to make the actors, state space, game dynamics, starting conditions, and action space explicit.

i) Actors

We’re refining the 3 players we mentioned above & their strategic profiles using the following names:

The “slow incumbent” - Capital-rich, process-heavy, optimized for distribution over rapid product change

The “balanced PMF” startup - Captures teams pushing toward parity on product while steadily testing channels.

The “all-in product” startup - Models a startup racing to close the product gap against the incumbent, still keeping a minimal acquisition drumbeat; this stresses whether superior product velocity plus modest distribution can tip share before runway decay.

ii) States

Each company will only care about 2 pieces of information:

How many customers they have

How much time they have in their time bank

For the sake of clarity, as time can be converted into money and reciprocally, we will only speak about time in this example.

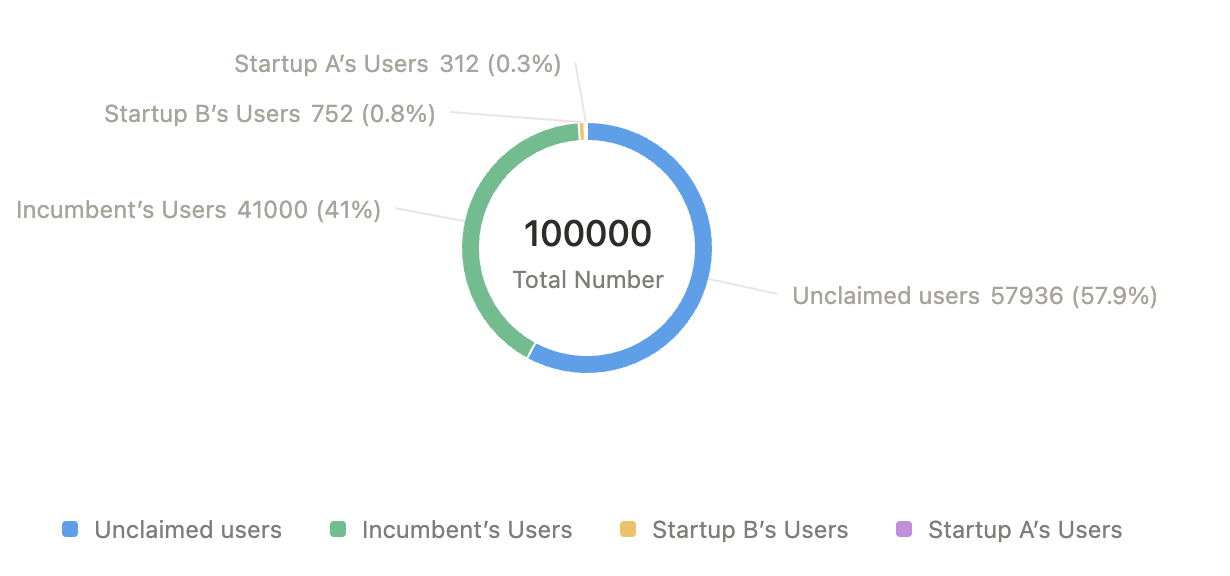

Furthermore, we assume a market of 100’000 prospects fixed.

Note: we’re furthermore assuming that each prospect uses one and only one solution (so it’s a zero-sum setup assuming the “no solution” is a player).

Example of user distribution among players for a market of 100’000 prospects.

iii) Decision-making framework for Customers & Perceived Product Value

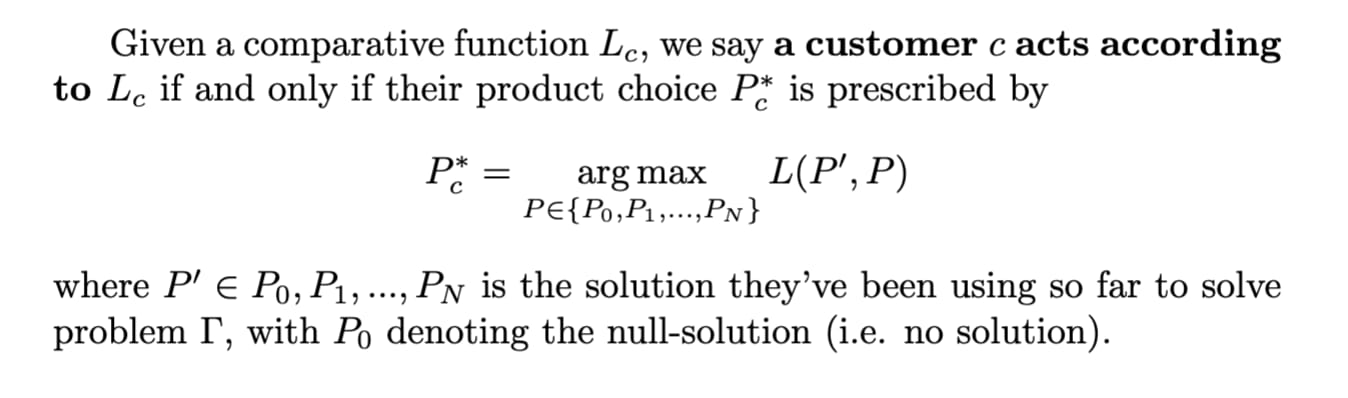

The way customers decide on a product is based on the notion of comparative function, i.e., a function that compares 2 solutions A & B. The customer then picks the one that has the higher value.

Mathematically, this is what it means for a customer to pick a solution.

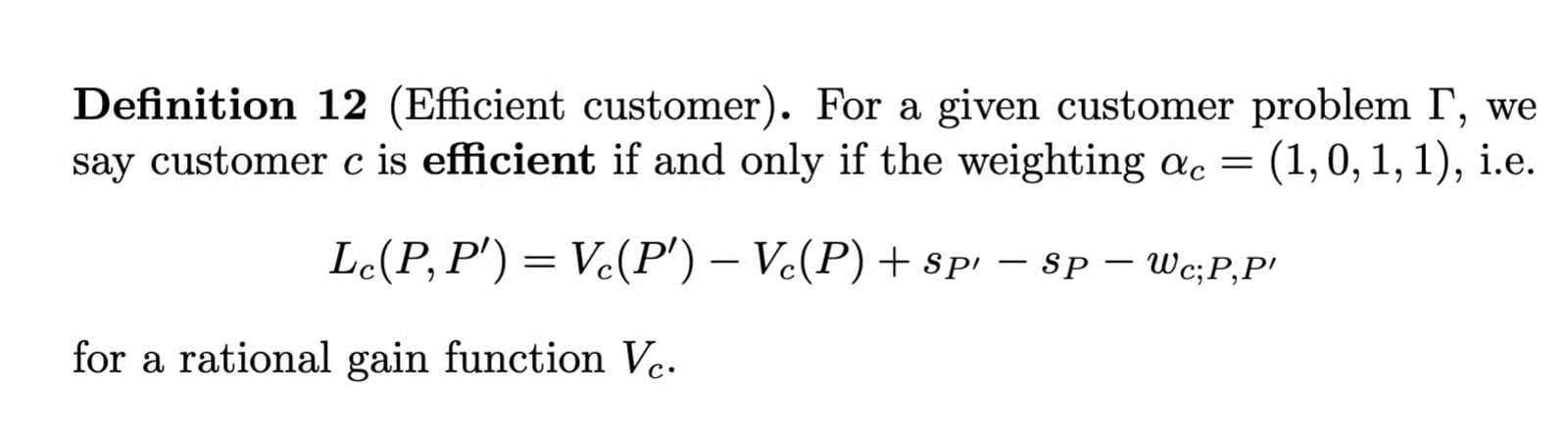

To make things smooth & simple while still being very realistic, we’re assuming to be in a situation where the homogeneous efficient customers hypothesis (HECH) condition holds. In a nutshell, it says that the switching costs are equal between any two solutions. This implies that comparative functions L_c are the same (for more details, see customer decision-making frameworks).

From the customer perspective, then, because of HECH, customers only care about the best product & its price, i.e, they care only about product quality and price.

Mathematically, L_c is what we mean by comparative function.

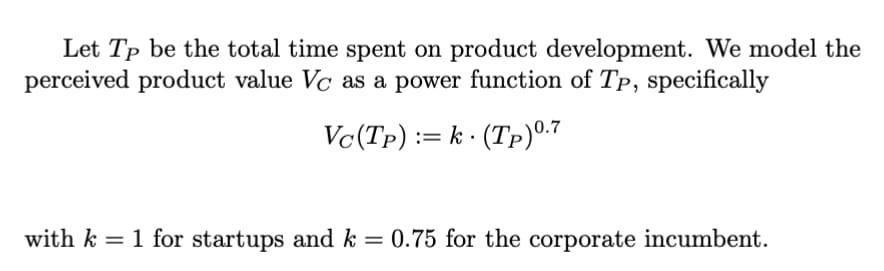

Finally, regarding the perceived product value V_c, we want it to scale rapidly at the start, but then slow down due to diminishing returns (e.g., bureaucracy, 80-20, etc). We also want to reflect that incumbent products often feel outdated (the original skeleton was built years ago, and it shows) compared to startup products (which are more modern). For that, we add a 25% handicap to incumbent products.

vi) Game dynamics

Each new customer at a startup brings 0.1 unit of time per week.

Each startup spends 1/100th of its total bank per week (heuristic: 2 years of runway).

We add the terminal conditions that a startup dies if it reaches less than 1 unit of time in the bank.

v) Starting conditions & further assumptions

For the time being, taking the heuristic that startups raising $4M plan for 24 months of runway, both startups above will start with a bank of 100 time units. Using assumption 5 of section ii), this means they will spend 1 unit of time per week.

The incumbent player starts with 50’000 units of time (heuristic for this number: incumbents have $500M-$50B of cash to work with per year, translating into 250-2500x more cash per month than startups. We’re considering the 500x case here)

Startups start with 0 customers and 0 time in product.

The incumbent player starts with 50% of the market & has already invested 100’000 time units in the product (heuristic: 10 years of history, approx 150 employees, with half focused on product. Using an exponential extrapolation, we are at around 100’000 units of time.)

vi) Admissible Actions

Regarding allowed actions, we restrict ourselves to the case where startups can only do the following two things:

Acquire more users or

Improve their product

There are countless ways to improve a product or acquire users, each with distinct maths & structure. For now, we focus on the most common, the simplest, yet also one of the most important classes: linear actions.

2) Introducing linear actions & strategies, aka “the things everybody does”

i) Introducing linear actions

We define linear actions as those that are such that 1 unit of time always returns a constant output, independently of the date. In our example, this means a constant number of phone calls with prospects or a constant delta in product improvement, whether you spent that unit of time today or in 3 months.

We’re going to call such actions linear (as their returns scale linearly with time).

ii) Introducing 2 families of linear strategies

We now distinguish between 2 families of strategies a startup can consider

Pure linear strategy - a company following a pure linear strategy periodically allocates the same percentage of its monthly resources on acquisition & product

Mixed linear strategy - a company might change from month to month how much of their resources are allocated to product versus distribution

For the sake of simplification, this toy example will only feature “pure” strategies, i.e., all players will repeatedly invest a fixed percentage of their monthly resource into both acquisition and product, respectively, every month.

3) Assigning strategies to Players

With the setup defined, we assign pure linear strategies to each actor as follows.

The slow incumbent (25% product, 75% acquisition):

Capital-rich, process-heavy, optimized for distribution, with established channels and a large installed base; product change rate is steady but moderate.

The balanced PMF seeker (50% product, 50% acquisition):

Captures teams pushing toward parity on product while steadily testing channels

The all-in product startup (70% product, 30% acquisition):

Models a startup racing to close the product gap against the incumbent, still keeping a minimal acquisition drumbeat; this stresses whether superior product velocity plus modest distribution can tip share before runway decay.

4) And…

I’m running out of characters! (Already at 1300 chars 🥲)

(I want these to be readable in 5’ to be more pleasant for you guys 🫶🏼)

In Part 2, we’re going to simulate the slow incumbent, balanced PMF seeker, and all‑in product startup under HECH, tracking customer flows and bank dynamics.

What is going to happen, you think? Have linear strategies been working for you in your startup? If yes, how? If not, why? What has your intuition been telling you? 🤔

Which "Startup Game Theory" piece do you want us to write about next? 🤔

- Co-founder matching as a RL-policy distance mapping

- The Startup Investor Game seen as poker

- Mathematical Definition of the Startup Investor Game

- Mathematical Definition of the Startup Founder Game

- Mathematical Definition of the Startup Operator Game

- The Maths of scoping for business opportunities

- Founder Winning Gameplays

- Comparing the Monetisation-Growth tradeoff to optimal Starcraft II Strategies

💌 Your Move

The game gets easier the more players join.

👉 Share this with one sharp friend — the bigger the network, the faster we all win. ⚡

(P.S. If you’ve got feedback or want me to analyse a specific situation, just hit reply — I read every message 😎)